A Random Ramble - Dissociation and Delving Deeper into Our Disability

- Michelle

- Aug 4, 2025

- 12 min read

I’m looking to get more into research and observations of dissociation and its adaptations for trauma, using personal life experiences from both myself and John. This topic really fascinates us and helps us tackle the struggles we have lived with for most, if not all, of our lives. This ramble provides a light overview of what I’ve been working through, collecting, and observing… and finally compiling everything to use as a foundation for the next round of research and observations.

I'm trying to get more into writing, but the fear of not expressing everything I intended—or doing so in a way others would understand—hinders me. Too often, I've received responses like, “What about this...?” only to realize I left something out. I could have written another page or two, but I was trying to summarize.

I learn better when I try to teach what I’ve learned and gathered, so I need to compile what I’ve collected more often to solidify new knowledge.

A lot of these topics have been swirling in my mind for years and have been constant subjects of discussion between John and me.

For example, the topic of time dilation is one we’ve explored more deeply, especially as we observe the pace of life for adults versus that of children. The intensity of impact for a child within an hour can be equal to what an adult might experience over months or even years of similar intensity.

Then there's the growing public understanding of the inner child—meaning the memories, sensations, and experiences from childhood that become the foundation of adult life. For some, a completely disconnected part of themselves.

Pair that with Internal Family Systems (IFS), a therapy modality that works with “parts.” Though it was once more associated with treating DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder), it has since become more mainstream and widely applicable.

I've been making more connections between this and my therapy work—especially since observing, starting in May, that adults often do not protect children well. They also tend to forget the dramatic difference in time perception once they reach a certain age. I still reflect on the moment a child learns to understand what “a year” means through mental and physical understanding—that’s often when the internal strain begins.

When a child finally can look back and refer to something that happened “ten years ago,” they start to forget that small, daily moments still have a significant impact. But with so many things happening from so many directions as an adult, you begin to mute or ignore a lot—just to stay sane. Our brains simply don’t have perfect memory systems or the capacity for it.

So, if a child is silently suffering abuse at home, how much does that suffering grow if it's overlooked throughout their entire childhood and young adult years?

I’m exploring this more deeply because this is what happened to me—and to John, too, in many ways.

I recently took a mental health assessment with my trauma therapist called the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation (MID). I believe the version I took had about 180 questions and took up most of our session. The assessment explores the specifics of dissociative symptoms—like amnesia, depersonalization (DP), derealization (DR), identity confusion, and identity alteration—while screening for dissociative disorders such as DID and OSDD (Other Specified Dissociative Disorder).

This test was incredibly important for me. It helped me finally put to rest the constant, unsettling thought that maybe I had DID.

I definitly have DP/DR which is Depersonalization and Derealization. Depersonalization is the "you don't feel real". Derealization is "the world around you doesn't feel real".

I’ve had two professionals trained in diagnosing dissociative disorders—and two people with DID themselves—seriously question whether I might have it. That really started to worry me...

After analyzing my life daily over the past six months, I realized I’ve had many experiences that could potentially cause dissociation. Neglectful parents. A creepy uncle who stayed over multiple times a year. And one incident of sexual assault by him that I do clearly recall. But I have no solid memory or evidence to confirm that claim of meeting a traumatic encounter as a young child to reach DID. Because in that incident I was able to escape. It’s possible the memory is blocked and could surface through somatic trauma work—but as of now, nothing concrete.

Throughout our entire marriage, it’s been evident that I relate extremely well to people who do have DID—my husband, my brother-in-law, a friend, even a former counselor.

But according to the MID, I scored a big zero for DID.

However, I do experience severe dissociation—enough to be on the cusp of DID. Just not a full separation of parts. My therapist described it more as “functional dissociation,” meaning I have parts of me that are always in Freeze, always in Fight, always in Fawn—and, due to CPTSD, also parts that Attach and Submit.

This is still a theory, but so far, it’s the explanation that best aligns with what I’ve been through and what I continue to experience—starting around the age of 11.

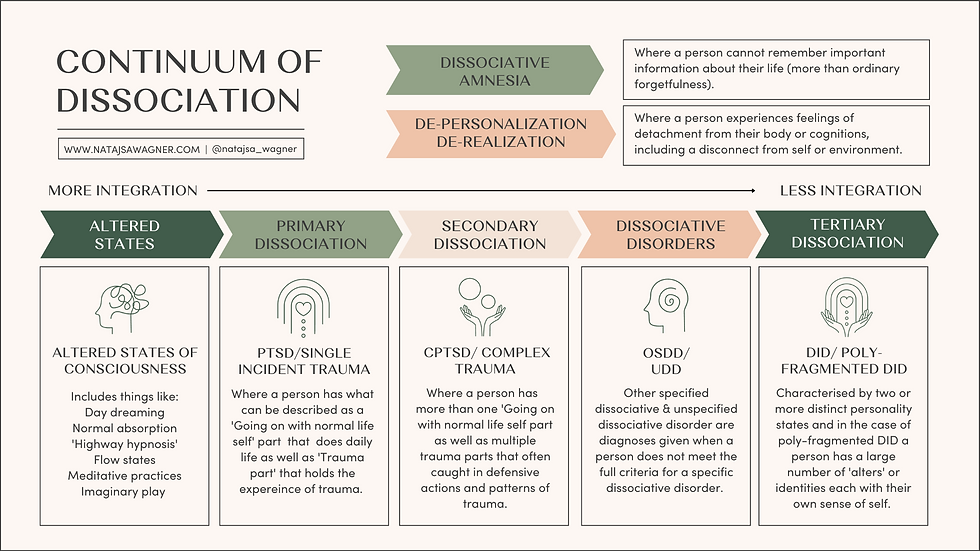

So this graphic goes a little over the basics of dissociation and the range of experiences within it. I wanted to go over a bit more of why this is a disability and not just a shared experience that "everyone goes through."

This brings me to a lovely clip from an Autistic therapist and advocate who was explaining the difference between a "Shared HUMAN Experience" and a "Debilitating HUMAN Experience."

She's adorable, and I would highly recommend visiting her channel:🔗 https://www.youtube.com/@Kaelynnism

I just discovered her through another YouTuber, who was going over the TikTok trend of assuming that various human experiences are "signs of [insert severe diagnosis here]." This applies to many diagnoses, as there seems to be a very common clout-chasing trend attaching itself to every struggle—struggles that people are trying to bring more awareness to, so those suffering can find help and support.

Kaelynn states it well:

"Something we can all agree on is that hypothetically, if you could speak German, that alone would not mean that you are German. But somehow, something everyone seems confused about is that just because you do an autistic thing, that alone does not mean that you are autistic. As it relates to human behavior, individual humans do not belong to behaviors. Instead, human behavior belongs to humans. Humans pace and sing and cry and throw stuff. 'Do you do this thing?' will forever be the wrong question. What matters is: to what degree do you do this thing? Everyone gets upset, but not everyone has a meltdown. Everyone fidgets, but not everyone engages in stereotypy. Everyone struggles with being understood from time to time, but not everyone struggles to communicate. I was diagnosed with autism at the age of 10. And when you ask if it's weird that you relate to my videos, the answer is no. It would be more weird if you didn’t relate at all. In conclusion, it’s not a matter of if you do the thing. It’s a matter of to what degree does the thing do you, and if your you is supered up, then you may in fact have a disability. With that in mind, if you can look at yourself objectively, do research, and serious self-reflection, many professionals actually accept self-diagnosis when it comes to autism."

The key part of determining whether something is a disability or just a “thing people do” comes down to three key factors:

Frequency – How often it happens

Intensity – How strongly it happens

Distress – How much it interferes with life

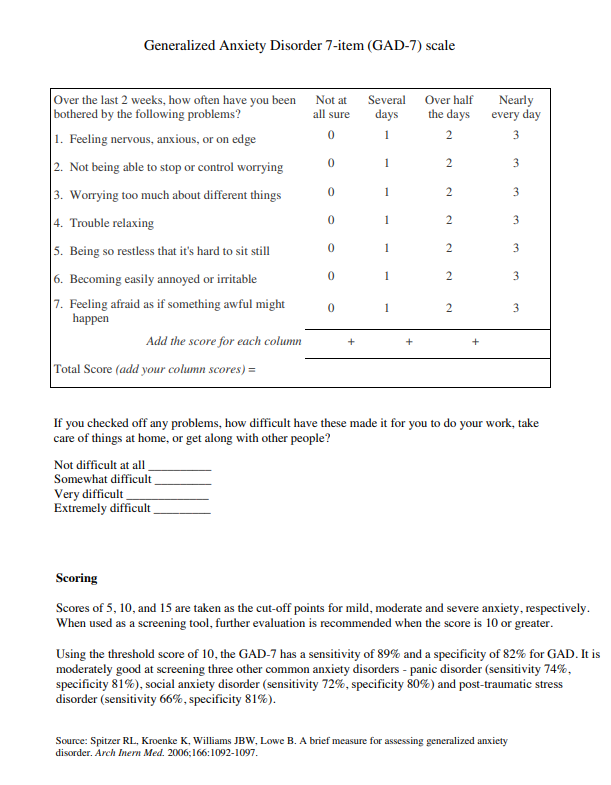

As an example, let me go over the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) basic questionnaire that is now commonly asked at every primary care provider (PCP) appointment.

Looking at this page, you'll see that there are only seven questions, each answered on a scale from “Not at all” to “Nearly every day.” Each answer is assigned a point value that is tallied at the end.

Just seeing how this is formatted can help clarify what counts as "normal behavior" versus "debilitating behavior." Any person will experience all of these at some point in life, usually in a context that makes sense—like “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge” before giving a big speech. Once the speech is over and the anxiety subsides, that’s a normal process and reaction.

But what happens when you feel that same level of fear all the time—even for something as small as going to the store to pick up eggs for a recipe?

For anxiety—at least for me—I have almost always been at “Nearly Every Day” for over twenty years for all seven of the items on the GAD questionnaire. Many of those symptoms spike multiple times a day, resulting in a constant internal emotional conflict that I’m fighting all the time. It causes ongoing fatigue and exhaustion.

My social anxiety is so severe that just thinking about going out the door causes extreme spikes of anxiety and fear. I’ve stayed paralyzed in my room for about a decade with severe anxiety and depression—watching friends and strangers reach their typical growth milestones while I hid away.

This is debilitating.

The Frequency was all the time—almost nonstop. Very few days in a month would I experience only minimal symptoms, and maybe one day with no anxiety or worry at all.

The Intensity would emotionally, mentally, and physically drain me within minutes. This could leave me bedridden and unable to move for hours or even days.

The Distress comes from the level of internal “uncomfortability” (to outright pain) that it causes in my life. I was either shut down or crying most of my life because of this.

This impacts my ability to work, my ability to socialize, my sense of time, and my capacity to enjoy life.

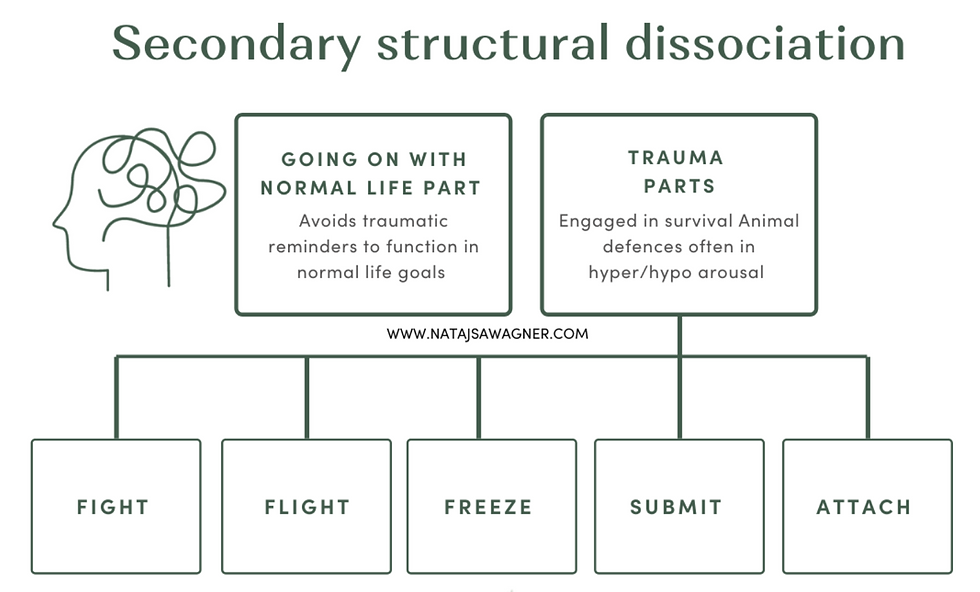

Now, going back to dissociation—specifically Secondary Structural Dissociation (the middle of the dissociation continuum). Complex trauma results from multiple or ongoing traumatic events during childhood. These are survival adaptations that develop when you cannot rely on your caregivers to meet your needs.

This is where my CPTSD sits—mostly pushing toward DID, except all of my “parts” are integrated and don’t have their own identities. But I do have noticeable shifts. The most obvious is when I’m angry or in “Fight” mode. I can lose connection and control, even though I’m generally aware of what’s going on. It terrifies me to be mentally present while my body and words are moving without thought or hesitation.

“Flight” swings with “Freeze” depending on the situation. I will either run physically or mentally pull out (disconnect from reality). I think the difference is that with “Flight,” I’m able to have thoughts and make plans to escape. “Freeze” can mean mental blanking—like during confrontation—or lying in bed completely unable to move. Not just mindlessly scrolling, but actually feeling a physical pressure pressing down on me, making it feel impossible to move.

My therapist also discussed two other trauma responses—ones that she explained are only available options during childhood: “Submit” and “Attach.” I believe this is where trauma bonding comes in as a survival necessity. It becomes a form of appeasement toward the threat in order to keep going.

This second, similar chart shows examples of how dissociation can manifest in different parts and what roles they play. Having these parts always active is exhausting.

I'm always hypervigilant, constantly worried about dangers around me. Normally, as an adult or when you're out of the abusive situation, it would make sense to retrain your body to adapt and move out of that—now harmful—defensive mechanism. Except, even as an adult, I’ve encountered more traumatic events that have kept this in place.

I'm always looking for an escape—staying away from people, places, situations... and even books, shows, and movies—because of possible triggers that could throw my emotions out of whack. A lot of this will need to be unraveled through trauma work, with the help of a trained trauma therapist.

I'm always frozen out of fear. I’m scared of being seen—or even perceived. It took me so much time and effort just to thank my friend's mom. I wanted her to know that I was grateful, but I didn’t want her to know that I said anything. Weird, isn’t it? I’m scared of making a sound, of being seen, of catching anyone’s attention. My sister even shared her experience with me, and some of the descriptions and sentences she used… are the same ones I’ve fought with on my own for years.

The Submit and Attach responses have faded the longer I’ve been out of my parents’ home. However, I can still see remnants of how those patterns have molded my personality and adaptations in managing my own home and marriage. I do a lot of self-sacrificing and automatically become a caretaker for almost anyone I encounter. With Attach, I’ve flipped to almost never wanting it—because of how often I’ve been abandoned, ignored, or forgotten. It always felt safer to just not expect anyone to stick around. The only person who’s really challenged that was John—and even then, the knee-jerk reaction only started to fade after a few years together.

So even today, four of these parts are still very active—controlling and directing me in the directions that are “acceptable.” In therapy, I have to work through the distressing somatic issues, because intellectualizing it—just mentally understanding what’s going on—doesn’t actually change anything. It doesn’t even mean you’ll be able to fix anything just because you know about it.

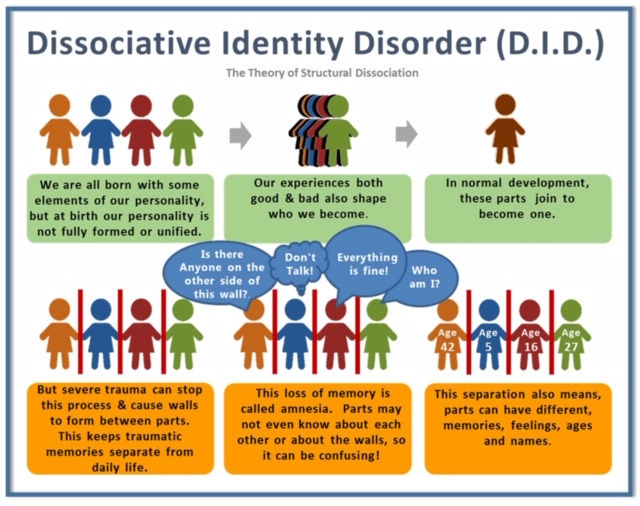

Now let’s start dipping into the least integrated range of dissociation—called DID.

John has DID and has shared it with me since the first few weeks of meeting. It has been a long time and a lot of effort adapting and learning of an even more severe condition.

Now, John said I can mention more about his struggles, but I’m on the fence about how much to divulge—mostly because I don’t want to speak too much about something I haven’t personally experienced and risk giving inaccurate information.

A quick note: We do not use the term “alters” because, to us, it implies “completely different bodies.” We use the term “facets” because, while they are all facing in different directions as distinct identities, they are all part of the same body.

These facets were born through severe, conscious-ripping trauma. When a child has no means to protect themselves and is pushed beyond their limit, their consciousness disconnects from the body as a last-ditch effort to protect the self. Each split forms from a different situation that caused the mind to separate.

This allows one facet to hold the memory of the traumatic incident while the rest of the consciousness continues on with life. That’s where the amnesia—forgetting large parts of your life—comes in as a coping mechanism.

The only problem is that just not mentally remembering does not remove the physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual impact of the event. The trauma still gets stored in the body, hopefully to be dealt with later in a safer time.

John has very impaired memory in many areas. One of those is long-term versus short-term memory. His short-term memory is lacking because his memory is stored very differently due to the splits. He doesn’t remember things in chronological order. So, if you say something to him, even just a few minutes ago, he can’t always recall whether it happened recently or years ago. Some long-term memory is protected but then again, it isn't stored chronologically so it doesn't quite help when needing to reference time.

For example: I’ve cleaned and moved items arond the home over the course of five years, telling and showing him every time things have changed—like where we store the scissors or hot glue. Later, he’ll be looking for something and vaguely recall it being in one area… only for me to remind him that the location had changed several times since it was last there.

It’s very frustrating for me too, but it’s understandable due to the trauma. It’s something we’ve had to accept and come to terms with. So, I tend to do as much of the remembering as I can of where everything is.

Not every facet communicates with the others, which leaves whoever is hosting bewildered about what’s going on.

By “hosting”, I mean the facet that is generally leading and controlling the body. There can be co-hosting, but that may include internal conflict based on each facet’s preferences.

That also means that each facet has their own interests, personality, likes/dislikes, and ways of speaking, etc. I’ve had to learn about each of them and adapt to what they need.

In DID, I believe there is almost always a “Little.”

By “Little,” we’re referring to the youngest child who experienced trauma. I believe it’s usually a child under the age of six (?) for this part to appear. The part that takes over at that point is usually 'the' or 'a' Protector facet that holds the actual trauma. There can be more than one Protector facet.

John, himself, says he is a facet that popped up later on—after about four other facets came before him. Two of those are now gone, while a few others remain.

I’ll let John and the system speak for themselves when the time is right. One other facet has recently gained enough courage to be present during therapy sessions, so it’s still pretty early to introduce them all to anyone.

------------------------------

If you are interested in learning more about Trauma, Dissociation, DID and more, I recommend these books we have gone into:

Bessel Van Der Kold M.D. - "Body Keeps the Score"

Robert Rich, M.Sc., Ph.D., M.A.P.S., A.A.S.H. - "Got Parts?: an Insider's Guide to Managing Life Successfully with Dissociative Identity Disorder"

Wings Foundation - "Survivors' & Loved Ones' Guide to Healing (3rd edition)"

------------------------------

Now this is just a start. Something I have been meaning to write down so I can move forward with the next steps of research. It's just so much information I need to solidify in some manner so I know what I'm working with and can tweak it when it's time.

But as for now, I hope it was at least a little informative on what we are going through and the level of severity that exists in our lives.

Thanks for reading and sticking around!

Comments